Until We Get It Right

We keep going. We write and re-write. We tinker and toil until the thing reaches a level of “right” we can deal with. Then, we send it out there.

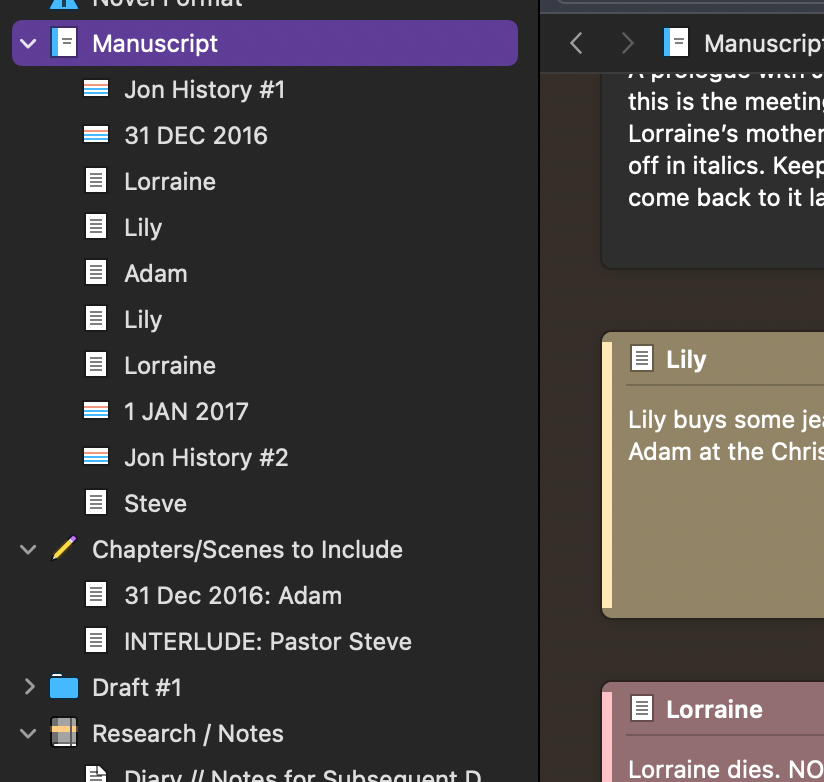

I’m working through a revision of a novel right now. It’s somewhere between a wholesale re-write and a touch-up. This is due, in part, to George Saunders’s “energy meter” method. While I use Ulysses for writing blog posts, keeping notes, and writing down ideas as they come, serious novel work happens in Scrivener. Ulysses serves as a sort of writer’s notebook for me, but Scrivener organizes all of that stuff into drafts and revisions.

I write in Ulysses every day, but Scrivener not so much. Therefore, I often forget how to do certain things in Scrivener. This afternoon was just such an occasion. I wanted to highlight a sentence that I knew wasn’t good enough yet, but I also didn’t want to dwell on it at the moment. I wanted to quickly mark it with some kind of flag that would allow me to come back to it later and fix it when I knew I had the time.

Like anyone, I Googled for Scrivener tips and decided an inline annotation — Shift+⌘+A on a Mac — would do the trick. But as I googled around, I discovered April Dávila’s blog (you can also find her on the Twitter: @aprildavila). I’m not familiar with Dávila’s work, to be honest. I’ve never read her novel, nor have I read any of her short stories. But two things drew me into her blog:

- Her posts are short and quick. (The opposite of what I often do here.)

- She has a menu option on her site called “Mindful Writing.”

If you know anything about me, then you these two words — “Mindful Writing” — would catch my eye. I obviously fancy myself a writer, yes, but I also teach meditation and consider myself a sort of mindfulness wonk. See, for example, my bio where I describe myself as a “Buddhiscopalian” (a term, to be honest, that I stole from Roseanne Cash).

I explored Dávila’s site and found some insightful posts, but I wanted to highlight a brief moment in one of them: “Talking Story with Charles Johnson.” If you’re not familiar with Johnson, I suggest you checkout Oxherding Tale (my favorite of his novels) and Middle Passage (winner of the National Book Award some thirty years ago). Johnson is an excellent write, a true literary giant.

In the post, Dávila recounts a class she took where Johnson was a guest. Specifically, she shares this quote from Johnson about why he loves writing:

Where else in life do you get to keep working at something until you get it right?

I’ll be honest: I don’t really even know what else Dávila said in the rest of her post. No fault of her own: she’s a wonderfully succinct writer (at least on her blog), and I deeply appreciate that. But I was so taken with this idea from Johnson that I couldn’t help but think about it.

Johnson is right, ya know?

In my life as a teacher, I rarely have an opportunity to get things exactly right. I have a very firm deadline: tomorrow’s class. Over the course of time, many semesters, let’s say, I might be able to slowly perfect a particular unit or some lesson. But it never seems to work that way. The life of a high school teacher can be chaotic, especially at an independent school where we are often asked to don too many hats. I may not get a chance to reflect on the effectiveness of this particular class because I’m too busy responding elsewhere, putting out fires, hatching new plans, keeping the work of the school moving forward.

While I teach my students to be reflective, while I encourage them to slow down and lean into the process, I don’t always get to do that myself.

In my writing, however, I can. While I may have deadlines from time to time, most of them are artificial and self-imposed. Most of the time, I have no set deadline. I’m working on this story until I get it right. More accurately, I’m working on this story until I get it as right as I can. (I doubt even Johnson would quibble with me if I told him I believed in a sort of asymptote of right-ness.)

Dávila’s story, published on her blog nearly five years ago, couldn’t have come at a more encouraging time for me. Funny how the world of the World Wide Web works that way: no regard for time and space, information and ideas just waiting in the ether until their moment arrives.

For this revision project, I’ve started with a blank manuscript in Scrivener. I create a new document, and then I add to it. Some of those additions are copied and pasted from the first draft. Others, however, are re-written from scratch. Each new scene gets worked over multiple times. On some days, the draft grows by as much as 1,200 words. On others, however, I see that I’ve only grown it by 75.

I’m currently about 10,000 words into this revision project. I estimate that this is between 12% and 15% of where the final novel will be. Some days, it feels like a hell of a lot. Other days, it feels like I’m just beginning.

In reality, I know I’m just beginning. I have no rush. Just keep working. It’s taken me about three weeks to get these 10,000 words in functional order. At that rate, I’ve got 15–20 weeks more before I’m approaching completion. That looks like a long time. I also know that this second draft is probably not going to be the final draft. I’m probably going to spend even more time trying to get it right.

I look at the months ahead, and it feels so long. Why can’t I just have this thing ready today? Why am I not sending it out to agents? Why can’t I just cut to the chase?

The beauty of writing, of course, is not in the idea of some finished product that gets published. The beauty is in this moment, working it through, making it a little more “right” (in the parlance of Charles Johnson) one word, phrase, clause, sentence, paragraph, page, scene, chapter at a time.

So, we keep going. We write and re-write. We tinker and toil until the thing reaches a level of “right” we can deal with. Then, we send it out there.

Then, we pick up another piece, spread it out in front of us, and work to get it right. We hope it might be even more right than the one that came before. After some time, we can look back and call it a career. But if we are engaged in the process — not so much focused on the results — then we might discover it is something more than a career.

It’s just life.